The West Highland Way ~ Scotland’s most popular and successful long-distance trail ~ was officially opened on 6 October 1980, but it took a few years for any kind of Race to germinate.

Step forward Duncan Watson (a not-so-well known athlete), who somewhat cheekily challenged Bobby Shields (a man with many trophies to his name, including the famed Ben Nevis hill race) to a head-to-head ‘race’ along the Way.

On 22 June 1985 the two of them gathered (a small and select gathering) at Milngavie railway station, and set off for Fort William. At that time the route differed in several ways from what we have today. In particular, the section from Balmaha to Rowardennan was pretty much all along the road; and the final section from Lundavra to Fort William was all on road. The actual mileage was therefore a bit less than today, and with considerably less up ‘n down along the journey. So in some ways it was “easier” than today’s route.

But on the other hand the route marking was not nearly as clear; and many stretches involved wading through deep mud and bog ~ especially from Beinglas farm up to the forest above Crianlarich. The ascent of Conic Hill, and the lower half of Glen Falloch, were certainly not the manicured paths that we now ‘enjoy’! So, in reality, the route was ‘different’ in several respects, rather than necessarily being much ‘easier’ or much ‘harder’. Neither man gave an inch in this titanic struggle. As they started to cross Rannoch Moor after c 60 miles they realised that, with this mindset, mutual destruction was the most likely outcome. So they pooled resources, and continued on to finish together in the fine time of 17 hours 48 minutes.

The Race was born!

In 1986 the two of them opened up the Race to some fellow runners – this time going from North to South, with Duncan as Race Director. He continued in this role up to and including 1989.

1987 saw a return to the South to North route; with 7 of the 11 runners completing the full distance.

The 1989 Race has gone into the history books as something of a “clash of the Titans” battle at the sharp end, with Dave Wallace completing the distance in an incredibly fast 15:26, just 6 minutes ahead of Mike Hartley. A report on this Race ~ the stuff of legend! ~ (along with many other Race write-ups over the years) can be found elsewhere on this website.

1989 also saw the first requirement for an official Scottish Athletics race permit; and the Race starting to evolve away from its early days back-of-an-envelope “come along and run” informality.

Peter White took on the organisation in 1990, to be succeeded by Jim Stewart in 1991 when the trail was re-routed to (much more closely) follow the present line:- c 95 miles distance (including c 14,760 feet of ascent, and c 14,760 feet of descent) of which about 8 miles is on road. Thus it is a bit longer than previously, and with considerably more up ‘n down.

Through the 1990s the Race continued on an annual basis, with Jim doing a great job in keeping it going. He fondly recalls all the enjoyment of these Races, and his marvelling at Brian Davidson’s 200 miles per week training regime. (This regime is not recommended for novices!) However, knowledge of the Race just tended to spread by word of mouth. Many of the early participants moved on to new pastures; but were not being replaced by new blood. The world at large just did not know of the Race’s existence; and it never quite reached critical mass insofar as numbers participating was concerned. At the end of the 1990s the event was seriously in danger of being discontinued through lack of uptake, and the gradually increasing burden of “safety requirements”, and related responsibilities, falling on the organisers’ shoulders.

However, two runners who had themselves completed the Race during the 1990s took the decision that this event was just “too much of a classic to die out and go away”. Step forward Dario Melaragni and Stan Milne.

The year 2000 saw a major boost (and possibly the survival of the event) with publicity surrounding very fast wins by both the men (Wim Epskamp 16:26) and the ladies (Kate Jenkins 17:37). This, as much as anything, raised the profile of the Race and brought it to a much wider audience.

Dario became, effectively, “Mr West Highland Way Race” during a ten year period at the helm (up to and including 2009) in which the event changed out of all recognition from its early days ethos of “just turn up @ Milngavie and run to Fort William, the first to get there being the winner”. He designed the first Race website, and was unstinting in his encouragement to new people to take up the challenge of doing the Race.

More participants (including many relatively “novice” runners) came on board, more formalised back-up support crews for runners, more organised checkpoints, mobile phone communications, first aiders, mountain rescue teams, Chris Ellis – the official ‘Race Doctor’, and much else besides, came into the equation. Dario took it all in his stride, but did not take kindly to the title “Race Director”, preferring in his quiet and unassuming way to simply be ‘the co-ordinator’ of it all. Sadly, neither Dario nor Stan is still with us; but their memory certainly lives on, and all involved with the race are greatly indebted to them.

Ian Beattie nobly stepped into the breach as Race Director for the 2010 race, following Dario’s untimely passing in July 2009, with the 2019 race marking Ian’s 10 years at the helm ~ ably assisted throughout by Adrian Stott and Sean Stone, Sean clocking c 20 years involvement with the race, Adrian nearly 30 years, while John Kynaston masterminds the website & techie side of things, and Ross Lawrie the artistic and graphic design “inspiration”. Many others help out, with more than 100 volunteers involved in the 2019 race. Worth particular mention are Murdo McEwan and Alan Kay, who stepped down after 10 years of service. Murdo was perhaps best known for handing out jelly babies at the 100k point, a part of the course now affectionately known as ‘Jelly Baby Hill’ (although his work in reviewing all the entries was also significant), and Alan looked after the Glencoe checkpoint. This latest 10 year period has seen an explosion of new ultra-distance events around the world; and a commensurate increase in numbers attracted to the sport. Who knows what the next 10 years might bring?!

From a few dozen runners starting each race in the early 2000s, and about half of them completing the distance, we now have well over 150 toeing the line each year at Milngavie, and about 75% finishing. 2012 saw a record 172 starting; but the persistent rain before and during the race lead to a lower %age completing the distance (119), compared to previous recent years. In 2013 starting numbers were up to 181, with 149 finishing. In 2014 these rose to 193 and 157 respectively. 2015 saw a slight drop ~ 155 finishers from 188 starting. 2016 (fine weather for racing) saw record numbers both starting @ 199; and finishing @ 159. In 2017, where strong wind and driving rain featured prominently, there were again 159 finishers, this time from 210 starters. For 2018 numbers were up again ~ 235 on the start line, 198 finishers. The high starters rate being partly explained by fewer entrants dropping out in the months leading up to race day; the high finishers rate due partly to the fine weather conditions for running, albeit maybe on the warm side for some. The temperature rose hugely during the following 24 hours; the numbers finishing may well have been rather lower if we’d had conditions like this. In 2019 a record 238 runners toed the start line; 196 finishing ~ very similar numbers to 2018, albeit probably more humid and muggy conditions after c 12 hours into the race.

Historically there had been considerable debate about record times, and the fastest time ever. On the 1991-onwards “present day route” Jez Bragg’s 15:44 (in 2006, shattering Wim’s 2000 record) was reduced by Terry Conway to 15:39 (2012); but the fastest ever remained Dave Wallace’s 15:26 in 1989. However, these were eclipsed by Paul Giblin’s 15:07:29 in 2013, and again in 2014 when Paul clocked an incredible 14:20:11. He improved on this yet again in 2015, bringing his record down to 14:14:44; and in doing so became the first person to win the race three years in a row. This 14:14:44 record was expected to stand for decades, but in 2017 Rob Sinclair (photo below) took the bull by the horns, already leading the rest of the field by 15 minutes at the first check point (Balmaha, 20 miles), and extending this lead throughout the journey to finish in 13:41:08, over 3 hours ahead of the second placed finisher. Sub 15 would have been inconceivable just a few years ago!

2017 also saw a slight change in the route along Loch Lomondside, shortly after Rowardennan, the new ‘low road’ replacing the previous ‘high road’. As to which of these may be shorter / faster the debate continues. The 2019 race saw another route change, this time the traditional Leisure Centre finish being replaced by the Nevis Centre, which also doubles up as the prize giving / goblets ceremony venue. This adds c ½ a mile distance (on flat tarmac); but hopefully much more of an “atmosphere” for folk finishing ~ especially for the last finishers as the venue is then fast filling up with people in readiness for the imminent awards ceremony.

For the ladies at the sharp end, Kate Jenkins’ 17:37:48 record in 2000 was brought down to Lucy Colquhoun’s 17:16:20 (in 2007), while in 2016 we had (for the first time) 3 ladies @ sub 19 hours, all being in the top 10 finishers overall ~ the 2016 winning lady (Lizzie Wraith in 17:42:27) moving to third lady on the all-time list. 2019 race first time runner Siobhan Killingbeck looked to possibly threaten Lucy’s record, being on schedule at Kinlochleven (80 miles), eventually finishing in 17:41:09 to just eclipse Lizzie’s 2016 time.

2016 race winner James Stewart (15:15:59) holds the M40 record, while the 2018 ladies winner, Nicola Adams-Hendry, brought the F40 record down to 17:55:41.

Following the 2019 Race a total of 1,429 people (affectionately known as ‘The Family’) have successfully completed the full race at least once. (Over 4,000 people have successfully summited Everest!) Adrian Stott, Jim Drummond, Tony Thistlethwaite, Fiona Rennie and Neil MacRitchie each with 15 finishes, head the number of race completions. Others with 10 or more cherished finishers’ engraved crystal goblets to their names: Alan Kay, Jim Robertson, , Pauline Walker, Alyson MacPherson, John Vernon, Bob Allison, Keith Hughes, Ian Rae, Rosie Bell, Derek Morley, Martin Deans, Jody Young, Andy Cole and (in 2019) Neil Rutherford. Alan Kay, John Vernon, Jim Robertson, and Neil MacRitchie hold the distinction of each having completed 10 WHW races in a row; while Neil Rutherford has completed 10 in a row, and all in under 24 hours!

Meanwhile, from the information available, we believe that Gareth Bryan-Jones held the title of “most senior finisher” for the men @ 70 years (2013 race) and Marian McPhail for the ladies @ 61 years (2015 race). But both of these were eclipsed in 2016 by Rob Reid (@ a slightly older 70 years young); and Norma Bone @ 64 years young; and then again by Norma in 2017 @ 65. The indefatigable Norma raised it again in 2018 @ 66. Norma was yet again on hand in 2019 to raise the ladies “most senior” record to 67 years, while Rob Reid returned and raised it for the men to 73 years. What a double-act inspiration these two good people are! On the subject of “senior” finishers, an honourable mention to Graham Arthur completing the 2018 race in 23:57:17 @ 70 years young (72nd finisher out of the 198). At the other end of the age spectrum it looks like Mark Collins is the “most youthful” finisher @ 21 years (2007 race).

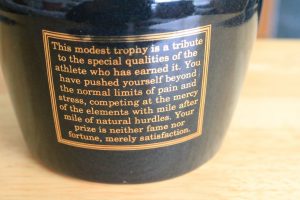

As a slight aside, the question has been asked if successful race finishers have always received engraved crystal glass goblets. In the early years race finishers seemed to receive whatever award the race organiser of the time decided, and got around to arranging. Up until 1988 there were no awards, apart from T shirts. In 1988 each finisher received a specially made WHW race water jug; in 1989 a personalised engraved paperweight; in 1990 a ‘Glasgow City of Culture 1990’ medal. But from c 1991 onwards it has always been an engraved crystal glass goblet, with very minor variations.

In 1989 a personalised engraved paperweight; in 1990 a ‘Glasgow City of Culture 1990’ medal.

But from c 1991 onwards it has always been an engraved crystal glass goblet, with very minor variations.

Murdo McEwan (after the 2019 race)